Table of Contents

- 13.1. Comparing Transaction and Nontransaction Engines

- 13.2. Other Storage Engines

- 13.3. Setting the Storage Engine

- 13.4. Overview of MySQL Storage Engine Architecture

- 13.5. The

MyISAMStorage Engine - 13.6. The

InnoDBStorage Engine - 13.6.1.

InnoDBContact Information - 13.6.2.

InnoDBConfiguration - 13.6.3.

InnoDBStartup Options and System Variables - 13.6.4. Creating and Using

InnoDBTables - 13.6.5. Adding, Removing, or Resizing

InnoDBData and Log Files - 13.6.6. Backing Up and Recovering an

InnoDBDatabase - 13.6.7. Moving an

InnoDBDatabase to Another Machine - 13.6.8. The

InnoDBTransaction Model and Locking - 13.6.9.

InnoDBMulti-Versioning - 13.6.10.

InnoDBTable and Index Structures - 13.6.11.

InnoDBDisk I/O and File Space Management - 13.6.12.

InnoDBError Handling - 13.6.13.

InnoDBPerformance Tuning and Troubleshooting - 13.6.14. Restrictions on

InnoDBTables

- 13.6.1.

- 13.7. The

IBMDB2IStorage Engine - 13.7.1. Installation

- 13.7.2. Configuration Options

- 13.7.3. Creating schemas and tables

- 13.7.4. Database/metadata management

- 13.7.5. Transaction behavior

- 13.7.6. Principles and Terminology

- 13.7.7. Notes and Limitations

- 13.7.8. Character sets and collations

- 13.7.9. Error codes and trouble-shooting information

- 13.8. The

MERGEStorage Engine - 13.9. The

MEMORY(HEAP) Storage Engine - 13.10. The

EXAMPLEStorage Engine - 13.11. The

FEDERATEDStorage Engine - 13.12. The

ARCHIVEStorage Engine - 13.13. The

CSVStorage Engine - 13.14. The

BLACKHOLEStorage Engine

MySQL supports several storage engines that act as handlers for different table types. MySQL storage engines include both those that handle transaction-safe tables and those that handle nontransaction-safe tables.

MySQL Server uses a pluggable storage engine architecture that allows storage engines to be loaded into and unloaded from a running MySQL server.

To determine which storage engines your server supports by using the

SHOW ENGINES statement. The value in

the Support column indicates whether an engine

can be used. A value of YES,

NO, or DEFAULT indicates that

an engine is available, not available, or avaiable and current set

as the default storage engine.

mysql> SHOW ENGINES\G

*************************** 1. row ***************************

Engine: FEDERATED

Support: NO

Comment: Federated MySQL storage engine

Transactions: NULL

XA: NULL

Savepoints: NULL

*************************** 2. row ***************************

Engine: MRG_MYISAM

Support: YES

Comment: Collection of identical MyISAM tables

Transactions: NO

XA: NO

Savepoints: NO

*************************** 3. row ***************************

Engine: MyISAM

Support: DEFAULT

Comment: Default engine as of MySQL 3.23 with great performance

Transactions: NO

XA: NO

Savepoints: NO

...

This chapter describes each of the MySQL storage engines except for

NDBCLUSTER, which is covered in

MySQL Cluster NDB 6.X/7.X. It also contains a

description of the pluggable storage engine architecture (see

Section 13.4, “Overview of MySQL Storage Engine Architecture”).

For information about storage engine support offered in commercial MySQL Server binaries, see MySQL Enterprise Server 5.1, on the MySQL Web site. The storage engines available might depend on which edition of Enterprise Server you are using.

For answers to some commonly asked questions about MySQL storage engines, see Section A.2, “MySQL 5.5 FAQ — Storage Engines”.

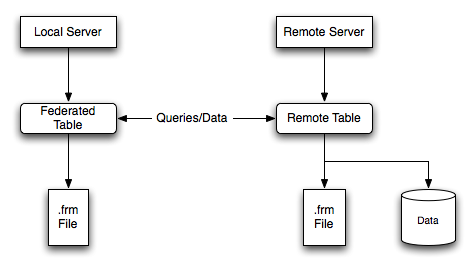

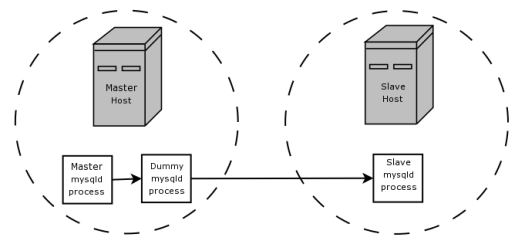

MySQL 5.4 supported storage engines

MyISAM— The default MySQL storage engine and the one that is used the most in Web, data warehousing, and other application environments.MyISAMis supported in all MySQL configurations, and is the default storage engine unless you have configured MySQL to use a different one by default.InnoDB— A transaction-safe (ACID compliant) storage engine for MySQL that has commit, rollback, and crash-recovery capabilities to protect user data.InnoDBrow-level locking (without escalation to coarser granularity locks) and Oracle-style consistent nonlocking reads increase multi-user concurrency and performance.InnoDBstores user data in clustered indexes to reduce I/O for common queries based on primary keys. To maintain data integrity,InnoDBalso supportsFOREIGN KEYreferential-integrity constraints.Memory— Stores all data in RAM for extremely fast access in environments that require quick lookups of reference and other like data. This engine was formerly known as theHEAPengine.Merge— Allows a MySQL DBA or developer to logically group a series of identicalMyISAMtables and reference them as one object. Good for VLDB environments such as data warehousing.Archive— Provides the perfect solution for storing and retrieving large amounts of seldom-referenced historical, archived, or security audit information.Federated— Offers the ability to link separate MySQL servers to create one logical database from many physical servers. Very good for distributed or data mart environments.CSV— The CSV storage engine stores data in text files using comma-separated values format. You can use the CSV engine to easily exchange data between other software and applications that can import and export in CSV format.Blackhole— The Blackhole storage engine accepts but does not store data and retrievals always return an empty set. The functionality can be used in distributed database design where data is automatically replicated, but not stored locally.Example— The Example storage engine is “stub” engine that does nothing. You can create tables with this engine, but no data can be stored in them or retrieved from them. The purpose of this engine is to serve as an example in the MySQL source code that illustrates how to begin writing new storage engines. As such, it is primarily of interest to developers.

It is important to remember that you are not restricted to using the same storage engine for an entire server or schema: you can use a different storage engine for each table in your schema.

Choosing a Storage Engine

The various storage engines provided with MySQL are designed with different use-cases in mind. To use the pluggable storage architecture effectively, it is good to have an idea of the advantages and disadvantages of the various storage engines. The following table provides an overview of some storage engines provided with MySQL:

Transaction-safe tables (TSTs) have several advantages over nontransaction-safe tables (NTSTs):

They are safer. Even if MySQL crashes or you get hardware problems, you can get your data back, either by automatic recovery or from a backup plus the transaction log.

You can combine many statements and accept them all at the same time with the

COMMITstatement (if autocommit is disabled).You can execute

ROLLBACKto ignore your changes (if autocommit is disabled).If an update fails, all of your changes are reverted. (With nontransaction-safe tables, all changes that have taken place are permanent.)

Transaction-safe storage engines can provide better concurrency for tables that get many updates concurrently with reads.

You can combine transaction-safe and nontransaction-safe tables in

the same statements to get the best of both worlds. However,

although MySQL supports several transaction-safe storage engines,

for best results, you should not mix different storage engines

within a transaction with autocommit disabled. For example, if you

do this, changes to nontransaction-safe tables still are committed

immediately and cannot be rolled back. For information about this

and other problems that can occur in transactions that use mixed

storage engines, see Section 12.4.1, “START TRANSACTION,

COMMIT, and

ROLLBACK Syntax”.

Nontransaction-safe tables have several advantages of their own, all of which occur because there is no transaction overhead:

Much faster

Lower disk space requirements

Less memory required to perform updates

Other storage engines may be available from third parties and community members that have used the Custom Storage Engine interface.

You can find more information on the list of third party storage engines on the MySQL Forge Storage Engines page.

Note

Third party engines are not supported by MySQL. For further information, documentation, installation guides, bug reporting or for any help or assistance with these engines, please contact the developer of the engine directly.

Third party engines that are known to be available include the following; please see the MySQL Forge links provided for more information:

PrimeBase XT (PBXT) — PBXT has been designed for modern, web-based, high concurrency environments.

RitmarkFS — RitmarkFS allows you to access and manipulate the file system using SQL queries. RitmarkFS also supports file system replication and directory change tracking.

Distributed Data Engine — The Distributed Data Engine is an Open Source project that is dedicated to provide a Storage Engine for distributed data according to workload statistics.

mdbtools — A pluggable storage engine that allows read-only access to Microsoft Access

.mdbdatabase files.solidDB for MySQL — solidDB Storage Engine for MySQL is an open source, transactional storage engine for MySQL Server. It is designed for mission-critical implementations that require a robust, transactional database. solidDB Storage Engine for MySQL is a multi-threaded storage engine that supports full ACID compliance with all expected transaction isolation levels, row-level locking, and Multi-Version Concurrency Control (MVCC) with nonblocking reads and writes.

BLOB Streaming Engine (MyBS) — The Scalable BLOB Streaming infrastructure for MySQL will transform MySQL into a scalable media server capable of streaming pictures, films, MP3 files and other binary and text objects (BLOBs) directly in and out of the database.

For more information on developing a customer storage engine that can be used with the Pluggable Storage Engine Architecture, see Writing a Custom Storage Engine on MySQL Forge.

When you create a new table, you can specify which storage engine

to use by adding an ENGINE table option to the

CREATE TABLE statement:

CREATE TABLE t (i INT) ENGINE = INNODB;

If you omit the ENGINE option, the default

storage engine is used. Normally, this is

MyISAM, but you can change it by using the

--default-storage-engine server

startup option, or by setting the

default-storage-engine option in the

my.cnf configuration file.

You can set the default storage engine to be used during the

current session by setting the

storage_engine variable:

SET storage_engine=MYISAM;

When MySQL is installed on Windows using the MySQL Configuration

Wizard, the InnoDB storage engine can be

selected as the default instead of MyISAM. See

Section 2.3.4.5, “The Database Usage Dialog”.

To convert a table from one storage engine to another, use an

ALTER TABLE statement that

indicates the new engine:

ALTER TABLE t ENGINE = MYISAM;

See Section 12.1.14, “CREATE TABLE Syntax”, and

Section 12.1.6, “ALTER TABLE Syntax”.

If you try to use a storage engine that is not compiled in or that

is compiled in but deactivated, MySQL instead creates a table

using the default storage engine, usually

MyISAM. This behavior is convenient when you

want to copy tables between MySQL servers that support different

storage engines. (For example, in a replication setup, perhaps

your master server supports transactional storage engines for

increased safety, but the slave servers use only nontransactional

storage engines for greater speed.)

This automatic substitution of the default storage engine for unavailable engines can be confusing for new MySQL users. A warning is generated whenever a storage engine is automatically changed.

For new tables, MySQL always creates an .frm

file to hold the table and column definitions. The table's index

and data may be stored in one or more other files, depending on

the storage engine. The server creates the

.frm file above the storage engine level.

Individual storage engines create any additional files required

for the tables that they manage. If a table name contains special

characters, the names for the table files contain encoded versions

of those characters as described in

Section 8.2.3, “Mapping of Identifiers to File Names”.

A database may contain tables of different types. That is, tables need not all be created with the same storage engine.

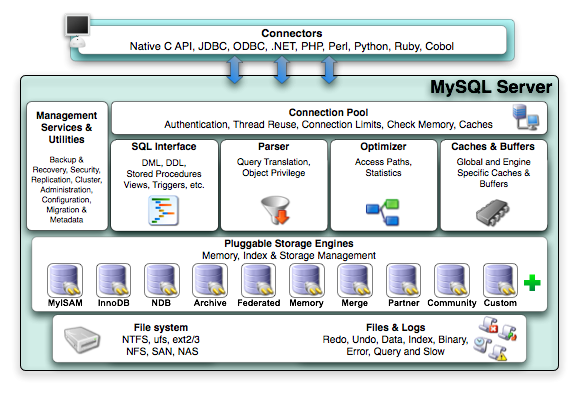

The MySQL pluggable storage engine architecture allows a database professional to select a specialized storage engine for a particular application need while being completely shielded from the need to manage any specific application coding requirements. The MySQL server architecture isolates the application programmer and DBA from all of the low-level implementation details at the storage level, providing a consistent and easy application model and API. Thus, although there are different capabilities across different storage engines, the application is shielded from these differences.

The MySQL pluggable storage engine architecture is shown in Figure 13.1, “MySQL Architecture with Pluggable Storage Engines”.

The pluggable storage engine architecture provides a standard set of management and support services that are common among all underlying storage engines. The storage engines themselves are the components of the database server that actually perform actions on the underlying data that is maintained at the physical server level.

This efficient and modular architecture provides huge benefits for those wishing to specifically target a particular application need — such as data warehousing, transaction processing, or high availability situations — while enjoying the advantage of utilizing a set of interfaces and services that are independent of any one storage engine.

The application programmer and DBA interact with the MySQL database through Connector APIs and service layers that are above the storage engines. If application changes bring about requirements that demand the underlying storage engine change, or that one or more additional storage engines be added to support new needs, no significant coding or process changes are required to make things work. The MySQL server architecture shields the application from the underlying complexity of the storage engine by presenting a consistent and easy-to-use API that applies across storage engines.

MySQL Server uses a pluggable storage engine architecture that allows storage engines to be loaded into and unloaded from a running MySQL server.

Plugging in a Storage Engine

Before a storage engine can be used, the storage engine plugin

shared library must be loaded into MySQL using the

INSTALL PLUGIN statement. For

example, if the EXAMPLE engine plugin is

named ha_example and the shared library is

named ha_example.so, you load it with the

following statement:

mysql> INSTALL PLUGIN ha_example SONAME 'ha_example.so';

To install a pluggable storage engine, the plugin file must be

located in the MySQL plugin directory, and the user issuing the

INSTALL PLUGIN statement must

have INSERT privilege for the

mysql.plugin table.

The shared library must be located in the MySQL server plugin

directory, the location of which is given by the

plugin_dir system variable.

Unplugging a Storage Engine

To unplug a storage engine, use the

UNINSTALL PLUGIN statement:

mysql> UNINSTALL PLUGIN ha_example;

If you unplug a storage engine that is needed by existing tables, those tables become inaccessible, but will still be present on disk (where applicable). Ensure that there are no tables using a storage engine before you unplug the storage engine.

A MySQL pluggable storage engine is the component in the MySQL database server that is responsible for performing the actual data I/O operations for a database as well as enabling and enforcing certain feature sets that target a specific application need. A major benefit of using specific storage engines is that you are only delivered the features needed for a particular application, and therefore you have less system overhead in the database, with the end result being more efficient and higher database performance. This is one of the reasons that MySQL has always been known to have such high performance, matching or beating proprietary monolithic databases in industry standard benchmarks.

From a technical perspective, what are some of the unique supporting infrastructure components that are in a storage engine? Some of the key feature differentiations include:

Concurrency — some applications have more granular lock requirements (such as row-level locks) than others. Choosing the right locking strategy can reduce overhead and therefore improve overall performance. This area also includes support for capabilities such as multi-version concurrency control or “snapshot” read.

Transaction Support — Not every application needs transactions, but for those that do, there are very well defined requirements such as ACID compliance and more.

Referential Integrity — The need to have the server enforce relational database referential integrity through DDL defined foreign keys.

Physical Storage — This involves everything from the overall page size for tables and indexes as well as the format used for storing data to physical disk.

Index Support — Different application scenarios tend to benefit from different index strategies. Each storage engine generally has its own indexing methods, although some (such as B-tree indexes) are common to nearly all engines.

Memory Caches — Different applications respond better to some memory caching strategies than others, so although some memory caches are common to all storage engines (such as those used for user connections or MySQL's high-speed Query Cache), others are uniquely defined only when a particular storage engine is put in play.

Performance Aids — This includes multiple I/O threads for parallel operations, thread concurrency, database checkpointing, bulk insert handling, and more.

Miscellaneous Target Features — This may include support for geospatial operations, security restrictions for certain data manipulation operations, and other similar features.

Each set of the pluggable storage engine infrastructure components are designed to offer a selective set of benefits for a particular application. Conversely, avoiding a set of component features helps reduce unnecessary overhead. It stands to reason that understanding a particular application's set of requirements and selecting the proper MySQL storage engine can have a dramatic impact on overall system efficiency and performance.

MyISAM is the default storage engine. It is based

on the older ISAM code but has many useful

extensions. (Note that MySQL 5.5 does

not support ISAM.)

Table 13.1. MyISAM Storage Engine

Features

| Storage limits | 256TB | Transactions | No | Locking granularity | Table |

| MVCC | No | Geospatial datatype support | Yes | Geospatial indexing support | Yes |

| B-tree indexes | Yes | Hash indexes | No | Full-text search indexes | Yes |

| Clustered indexes | No | Data caches | No | Index caches | Yes |

| Compressed data | Yes[a] | Encrypted data[b] | Yes | Cluster database support | No |

| Replication support[c] | Yes | Foreign key support | No | Backup / point-in-time recovery[d] | Yes |

| Query cache support | Yes | Update statistics for data dictionary | Yes | ||

[a] Compressed MyISAM tables are supported only when using the compressed row format. Tables using the compressed row format with MyISAM are read only. [b] Implemented in the server (via encryption functions), rather than in the storage engine. [c] Implemented in the server, rather than in the storage product [d] Implemented in the server, rather than in the storage product | |||||

Each MyISAM table is stored on disk in three

files. The files have names that begin with the table name and have

an extension to indicate the file type. An .frm

file stores the table format. The data file has an

.MYD (MYData) extension. The

index file has an .MYI

(MYIndex) extension.

To specify explicitly that you want a MyISAM

table, indicate that with an ENGINE table option:

CREATE TABLE t (i INT) ENGINE = MYISAM;

Normally, it is unnecessary to use ENGINE to

specify the MyISAM storage engine.

MyISAM is the default engine unless the default

has been changed. To ensure that MyISAM is used

in situations where the default might have been changed, include the

ENGINE option explicitly.

You can check or repair MyISAM tables with the

mysqlcheck client or myisamchk

utility. You can also compress MyISAM tables with

myisampack to take up much less space. See

Section 4.5.3, “mysqlcheck — A Table Maintenance Program”, Section 4.6.3, “myisamchk — MyISAM Table-Maintenance Utility”, and

Section 4.6.5, “myisampack — Generate Compressed, Read-Only MyISAM Tables”.

MyISAM tables have the following characteristics:

All data values are stored with the low byte first. This makes the data machine and operating system independent. The only requirements for binary portability are that the machine uses two's-complement signed integers and IEEE floating-point format. These requirements are widely used among mainstream machines. Binary compatibility might not be applicable to embedded systems, which sometimes have peculiar processors.

There is no significant speed penalty for storing data low byte first; the bytes in a table row normally are unaligned and it takes little more processing to read an unaligned byte in order than in reverse order. Also, the code in the server that fetches column values is not time critical compared to other code.

All numeric key values are stored with the high byte first to allow better index compression.

Large files (up to 63-bit file length) are supported on file systems and operating systems that support large files.

There is a limit of 232 (~4.295E+09) rows in a

MyISAMtable. If you build MySQL with the--with-big-tablesoption, the row limitation is increased to (232)2 (1.844E+19) rows. See Section 2.10.2, “Typical configure Options”. Binary distributions for Unix and Linux are built with this option.The maximum number of indexes per

MyISAMtable is 64. This can be changed by recompiling. You can configure the build by invoking configure with the--with-max-indexes=option, whereNNis the maximum number of indexes to permit perMyISAMtable.Nmust be less than or equal to 128.The maximum number of columns per index is 16.

The maximum key length is 1000 bytes. This can also be changed by changing the source and recompiling. For the case of a key longer than 250 bytes, a larger key block size than the default of 1024 bytes is used.

When rows are inserted in sorted order (as when you are using an

AUTO_INCREMENTcolumn), the index tree is split so that the high node only contains one key. This improves space utilization in the index tree.Internal handling of one

AUTO_INCREMENTcolumn per table is supported.MyISAMautomatically updates this column forINSERTandUPDATEoperations. This makesAUTO_INCREMENTcolumns faster (at least 10%). Values at the top of the sequence are not reused after being deleted. (When anAUTO_INCREMENTcolumn is defined as the last column of a multiple-column index, reuse of values deleted from the top of a sequence does occur.) TheAUTO_INCREMENTvalue can be reset withALTER TABLEor myisamchk.Dynamic-sized rows are much less fragmented when mixing deletes with updates and inserts. This is done by automatically combining adjacent deleted blocks and by extending blocks if the next block is deleted.

MyISAMsupports concurrent inserts: If a table has no free blocks in the middle of the data file, you canINSERTnew rows into it at the same time that other threads are reading from the table. A free block can occur as a result of deleting rows or an update of a dynamic length row with more data than its current contents. When all free blocks are used up (filled in), future inserts become concurrent again. See Section 7.3.3, “Concurrent Inserts”.You can put the data file and index file in different directories on different physical devices to get more speed with the

DATA DIRECTORYandINDEX DIRECTORYtable options toCREATE TABLE. See Section 12.1.14, “CREATE TABLESyntax”.NULLvalues are allowed in indexed columns. This takes 0–1 bytes per key.Each character column can have a different character set. See Section 9.1, “Character Set Support”.

There is a flag in the

MyISAMindex file that indicates whether the table was closed correctly. If mysqld is started with the--myisam-recoveroption,MyISAMtables are automatically checked when opened, and are repaired if the table wasn't closed properly.myisamchk marks tables as checked if you run it with the

--update-stateoption. myisamchk --fast checks only those tables that don't have this mark.myisamchk --analyze stores statistics for portions of keys, as well as for entire keys.

myisampack can pack

BLOBandVARCHARcolumns.

MyISAM also supports the following features:

Additional Resources

A forum dedicated to the

MyISAMstorage engine is available at http://forums.mysql.com/list.php?21.

The following options to mysqld can be used to

change the behavior of MyISAM tables. For

additional information, see Section 5.1.2, “Server Command Options”.

Table 13.2. MyISAM Option/Variable

Reference

| Name | Cmd-Line | Option file | System Var | Status Var | Var Scope | Dynamic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bulk_insert_buffer_size | Yes | Yes | Yes | Both | Yes | |

| concurrent_insert | Yes | Yes | Yes | Global | Yes | |

| delay-key-write | Yes | Yes | Global | Yes | ||

| - Variable: delay_key_write | Yes | Global | Yes | |||

| key_buffer_size | Yes | Yes | Yes | Global | Yes | |

| log-isam | Yes | Yes | ||||

| myisam-block-size | Yes | Yes | ||||

| myisam_data_pointer_size | Yes | Yes | Yes | Global | Yes | |

| myisam_max_sort_file_size | Yes | Yes | Yes | Global | Yes | |

| myisam_mmap_size | Yes | Yes | Yes | Global | No | |

| myisam-recover | Yes | Yes | ||||

| myisam_recover_options | Yes | Global | No | |||

| myisam_repair_threads | Yes | Yes | Yes | Both | Yes | |

| myisam_sort_buffer_size | Yes | Yes | Yes | Both | Yes | |

| myisam_stats_method | Yes | Yes | Yes | Both | Yes | |

| myisam_use_mmap | Yes | Yes | Yes | Global | Yes | |

| skip-concurrent-insert | Yes | Yes | ||||

| - Variable: concurrent_insert |

Set the mode for automatic recovery of crashed

MyISAMtables.Don't flush key buffers between writes for any

MyISAMtable.Note

If you do this, you should not access

MyISAMtables from another program (such as from another MySQL server or with myisamchk) when the tables are in use. Doing so risks index corruption. Using--external-lockingdoes not eliminate this risk.

The following system variables affect the behavior of

MyISAM tables. For additional information, see

Section 5.1.4, “Server System Variables”.

The size of the tree cache used in bulk insert optimization.

Note

This is a limit per thread!

The maximum size of the temporary file that MySQL is allowed to use while re-creating a

MyISAMindex (duringREPAIR TABLE,ALTER TABLE, orLOAD DATA INFILE). If the file size would be larger than this value, the index is created using the key cache instead, which is slower. The value is given in bytes.Set the size of the buffer used when recovering tables.

Automatic recovery is activated if you start

mysqld with the

--myisam-recover option. In this

case, when the server opens a MyISAM table, it

checks whether the table is marked as crashed or whether the open

count variable for the table is not 0 and you are running the

server with external locking disabled. If either of these

conditions is true, the following happens:

The server checks the table for errors.

If the server finds an error, it tries to do a fast table repair (with sorting and without re-creating the data file).

If the repair fails because of an error in the data file (for example, a duplicate-key error), the server tries again, this time re-creating the data file.

If the repair still fails, the server tries once more with the old repair option method (write row by row without sorting). This method should be able to repair any type of error and has low disk space requirements.

MySQL Enterprise

Subscribers to MySQL Enterprise Monitor receive notification if

the --myisam-recover option has

not been set. For more information, see

http://www.mysql.com/products/enterprise/advisors.html.

If the recovery wouldn't be able to recover all rows from

previously completed statements and you didn't specify

FORCE in the value of the

--myisam-recover option, automatic

repair aborts with an error message in the error log:

Error: Couldn't repair table: test.g00pages

If you specify FORCE, a warning like this is

written instead:

Warning: Found 344 of 354 rows when repairing ./test/g00pages

Note that if the automatic recovery value includes

BACKUP, the recovery process creates files with

names of the form

tbl_name-datetime.BAK

MyISAM tables use B-tree indexes. You can

roughly calculate the size for the index file as

(key_length+4)/0.67, summed over all keys. This

is for the worst case when all keys are inserted in sorted order

and the table doesn't have any compressed keys.

String indexes are space compressed. If the first index part is a

string, it is also prefix compressed. Space compression makes the

index file smaller than the worst-case figure if a string column

has a lot of trailing space or is a

VARCHAR column that is not always

used to the full length. Prefix compression is used on keys that

start with a string. Prefix compression helps if there are many

strings with an identical prefix.

In MyISAM tables, you can also prefix compress

numbers by specifying the PACK_KEYS=1 table

option when you create the table. Numbers are stored with the high

byte first, so this helps when you have many integer keys that

have an identical prefix.

MyISAM supports three different storage

formats. Two of them, fixed and dynamic format, are chosen

automatically depending on the type of columns you are using. The

third, compressed format, can be created only with the

myisampack utility (see

Section 4.6.5, “myisampack — Generate Compressed, Read-Only MyISAM Tables”).

When you use CREATE TABLE or

ALTER TABLE for a table that has no

BLOB or

TEXT columns, you can force the

table format to FIXED or

DYNAMIC with the ROW_FORMAT

table option.

See Section 12.1.14, “CREATE TABLE Syntax”, for information about

ROW_FORMAT.

You can decompress (unpack) compressed MyISAM

tables using myisamchk

--unpack; see

Section 4.6.3, “myisamchk — MyISAM Table-Maintenance Utility”, for more information.

Static format is the default for MyISAM

tables. It is used when the table contains no variable-length

columns (VARCHAR,

VARBINARY,

BLOB, or

TEXT). Each row is stored using a

fixed number of bytes.

Of the three MyISAM storage formats, static

format is the simplest and most secure (least subject to

corruption). It is also the fastest of the on-disk formats due

to the ease with which rows in the data file can be found on

disk: To look up a row based on a row number in the index,

multiply the row number by the row length to calculate the row

position. Also, when scanning a table, it is very easy to read a

constant number of rows with each disk read operation.

The security is evidenced if your computer crashes while the

MySQL server is writing to a fixed-format

MyISAM file. In this case,

myisamchk can easily determine where each row

starts and ends, so it can usually reclaim all rows except the

partially written one. Note that MyISAM table

indexes can always be reconstructed based on the data rows.

Note

Fixed-length row format is only available for tables without

BLOB or

TEXT columns. Creating a table

with these columns with an explicit

ROW_FORMAT clause will not raise an error

or warning; the format specification will be ignored.

Static-format tables have these characteristics:

CHARandVARCHARcolumns are space-padded to the specified column width, although the column type is not altered.BINARYandVARBINARYcolumns are padded with0x00bytes to the column width.Very quick.

Easy to cache.

Easy to reconstruct after a crash, because rows are located in fixed positions.

Reorganization is unnecessary unless you delete a huge number of rows and want to return free disk space to the operating system. To do this, use

OPTIMIZE TABLEor myisamchk -r.Usually require more disk space than dynamic-format tables.

Dynamic storage format is used if a MyISAM

table contains any variable-length columns

(VARCHAR,

VARBINARY,

BLOB, or

TEXT), or if the table was

created with the ROW_FORMAT=DYNAMIC table

option.

Dynamic format is a little more complex than static format because each row has a header that indicates how long it is. A row can become fragmented (stored in noncontiguous pieces) when it is made longer as a result of an update.

You can use OPTIMIZE TABLE or

myisamchk -r to defragment a table. If you

have fixed-length columns that you access or change frequently

in a table that also contains some variable-length columns, it

might be a good idea to move the variable-length columns to

other tables just to avoid fragmentation.

Dynamic-format tables have these characteristics:

All string columns are dynamic except those with a length less than four.

Each row is preceded by a bitmap that indicates which columns contain the empty string (for string columns) or zero (for numeric columns). Note that this does not include columns that contain

NULLvalues. If a string column has a length of zero after trailing space removal, or a numeric column has a value of zero, it is marked in the bitmap and not saved to disk. Nonempty strings are saved as a length byte plus the string contents.Much less disk space usually is required than for fixed-length tables.

Each row uses only as much space as is required. However, if a row becomes larger, it is split into as many pieces as are required, resulting in row fragmentation. For example, if you update a row with information that extends the row length, the row becomes fragmented. In this case, you may have to run

OPTIMIZE TABLEor myisamchk -r from time to time to improve performance. Use myisamchk -ei to obtain table statistics.More difficult than static-format tables to reconstruct after a crash, because rows may be fragmented into many pieces and links (fragments) may be missing.

The expected row length for dynamic-sized rows is calculated using the following expression:

3 + (

number of columns+ 7) / 8 + (number of char columns) + (packed size of numeric columns) + (length of strings) + (number of NULL columns+ 7) / 8There is a penalty of 6 bytes for each link. A dynamic row is linked whenever an update causes an enlargement of the row. Each new link is at least 20 bytes, so the next enlargement probably goes in the same link. If not, another link is created. You can find the number of links using myisamchk -ed. All links may be removed with

OPTIMIZE TABLEor myisamchk -r.

Compressed storage format is a read-only format that is generated with the myisampack tool. Compressed tables can be uncompressed with myisamchk.

Compressed tables have the following characteristics:

Compressed tables take very little disk space. This minimizes disk usage, which is helpful when using slow disks (such as CD-ROMs).

Each row is compressed separately, so there is very little access overhead. The header for a row takes up one to three bytes depending on the biggest row in the table. Each column is compressed differently. There is usually a different Huffman tree for each column. Some of the compression types are:

Suffix space compression.

Prefix space compression.

Numbers with a value of zero are stored using one bit.

If values in an integer column have a small range, the column is stored using the smallest possible type. For example, a

BIGINTcolumn (eight bytes) can be stored as aTINYINTcolumn (one byte) if all its values are in the range from-128to127.If a column has only a small set of possible values, the data type is converted to

ENUM.A column may use any combination of the preceding compression types.

Can be used for fixed-length or dynamic-length rows.

Note

While a compressed table is read only, and you cannot

therefore update or add rows in the table, DDL (Data

Definition Language) operations are still valid. For example,

you may still use DROP to drop the table,

and TRUNCATE TABLE to empty the

table.

The file format that MySQL uses to store data has been extensively tested, but there are always circumstances that may cause database tables to become corrupted. The following discussion describes how this can happen and how to handle it.

Even though the MyISAM table format is very

reliable (all changes to a table made by an SQL statement are

written before the statement returns), you can still get

corrupted tables if any of the following events occur:

The mysqld process is killed in the middle of a write.

An unexpected computer shutdown occurs (for example, the computer is turned off).

Hardware failures.

You are using an external program (such as myisamchk) to modify a table that is being modified by the server at the same time.

A software bug in the MySQL or

MyISAMcode.

Typical symptoms of a corrupt table are:

You get the following error while selecting data from the table:

Incorrect key file for table: '...'. Try to repair it

Queries don't find rows in the table or return incomplete results.

You can check the health of a MyISAM table

using the CHECK TABLE statement,

and repair a corrupted MyISAM table with

REPAIR TABLE. When

mysqld is not running, you can also check or

repair a table with the myisamchk command.

See Section 12.5.2.2, “CHECK TABLE Syntax”,

Section 12.5.2.5, “REPAIR TABLE Syntax”, and Section 4.6.3, “myisamchk — MyISAM Table-Maintenance Utility”.

If your tables become corrupted frequently, you should try to

determine why this is happening. The most important thing to

know is whether the table became corrupted as a result of a

server crash. You can verify this easily by looking for a recent

restarted mysqld message in the error log. If

there is such a message, it is likely that table corruption is a

result of the server dying. Otherwise, corruption may have

occurred during normal operation. This is a bug. You should try

to create a reproducible test case that demonstrates the

problem. See Section B.5.4.2, “What to Do If MySQL Keeps Crashing”, and

MySQL

Internals: Porting.

MySQL Enterprise Find out about problems before they occur. Subscribe to the MySQL Enterprise Monitor for expert advice about the state of your servers. For more information, see http://www.mysql.com/products/enterprise/advisors.html.

Each MyISAM index file

(.MYI file) has a counter in the header

that can be used to check whether a table has been closed

properly. If you get the following warning from

CHECK TABLE or

myisamchk, it means that this counter has

gone out of sync:

clients are using or haven't closed the table properly

This warning doesn't necessarily mean that the table is corrupted, but you should at least check the table.

The counter works as follows:

The first time a table is updated in MySQL, a counter in the header of the index files is incremented.

The counter is not changed during further updates.

When the last instance of a table is closed (because a

FLUSH TABLESoperation was performed or because there is no room in the table cache), the counter is decremented if the table has been updated at any point.When you repair the table or check the table and it is found to be okay, the counter is reset to zero.

To avoid problems with interaction with other processes that might check the table, the counter is not decremented on close if it was zero.

In other words, the counter can become incorrect only under these conditions:

A

MyISAMtable is copied without first issuingLOCK TABLESandFLUSH TABLES.MySQL has crashed between an update and the final close. (Note that the table may still be okay, because MySQL always issues writes for everything between each statement.)

A table was modified by myisamchk --recover or myisamchk --update-state at the same time that it was in use by mysqld.

Multiple mysqld servers are using the table and one server performed a

REPAIR TABLEorCHECK TABLEon the table while it was in use by another server. In this setup, it is safe to useCHECK TABLE, although you might get the warning from other servers. However,REPAIR TABLEshould be avoided because when one server replaces the data file with a new one, this is not known to the other servers.In general, it is a bad idea to share a data directory among multiple servers. See Section 5.6, “Running Multiple MySQL Servers on the Same Machine”, for additional discussion.

- 13.6.1.

InnoDBContact Information - 13.6.2.

InnoDBConfiguration - 13.6.3.

InnoDBStartup Options and System Variables - 13.6.4. Creating and Using

InnoDBTables - 13.6.5. Adding, Removing, or Resizing

InnoDBData and Log Files - 13.6.6. Backing Up and Recovering an

InnoDBDatabase - 13.6.7. Moving an

InnoDBDatabase to Another Machine - 13.6.8. The

InnoDBTransaction Model and Locking - 13.6.9.

InnoDBMulti-Versioning - 13.6.10.

InnoDBTable and Index Structures - 13.6.11.

InnoDBDisk I/O and File Space Management - 13.6.12.

InnoDBError Handling - 13.6.13.

InnoDBPerformance Tuning and Troubleshooting - 13.6.14. Restrictions on

InnoDBTables

InnoDB is a transaction-safe (ACID compliant)

storage engine for MySQL that has commit, rollback, and

crash-recovery capabilities to protect user data.

InnoDB row-level locking (without escalation to

coarser granularity locks) and Oracle-style consistent nonlocking

reads increase multi-user concurrency and performance.

InnoDB stores user data in clustered indexes to

reduce I/O for common queries based on primary keys. To maintain

data integrity, InnoDB also supports

FOREIGN KEY referential-integrity constraints.

You can freely mix InnoDB tables with tables from

other MySQL storage engines, even within the same statement.

To determine whether your server supports InnoDB

use the SHOW ENGINES statement. See

Section 12.5.5.17, “SHOW ENGINES Syntax”.

Table 13.3. InnoDB Storage Engine

Features

| Storage limits | 64TB | Transactions | Yes | Locking granularity | Row |

| MVCC | Yes | Geospatial datatype support | Yes | Geospatial indexing support | No |

| B-tree indexes | Yes | Hash indexes | No | Full-text search indexes | No |

| Clustered indexes | Yes | Data caches | Yes | Index caches | Yes |

| Compressed data | Yes[a] | Encrypted data[b] | Yes | Cluster database support | No |

| Replication support[c] | Yes | Foreign key support | Yes | Backup / point-in-time recovery[d] | Yes |

| Query cache support | Yes | Update statistics for data dictionary | Yes | ||

[a] Compressed InnoDB tables are supported only by InnoDB Plugin. [b] Implemented in the server (via encryption functions), rather than in the storage engine. [c] Implemented in the server, rather than in the storage product [d] Implemented in the server, rather than in the storage product | |||||

InnoDB has been designed for maximum performance

when processing large data volumes. Its CPU efficiency is probably

not matched by any other disk-based relational database engine.

The InnoDB storage engine maintains its own

buffer pool for caching data and indexes in main memory.

InnoDB stores its tables and indexes in a

tablespace, which may consist of several files (or raw disk

partitions). This is different from, for example,

MyISAM tables where each table is stored using

separate files. InnoDB tables can be very large

even on operating systems where file size is limited to 2GB.

The Windows Essentials installer makes InnoDB the

MySQL default storage engine on Windows, if the server being

installed supports InnoDB.

InnoDB is used in production at numerous large

database sites requiring high performance. The famous Internet news

site Slashdot.org runs on InnoDB. Mytrix, Inc.

stores more than 1TB of data in InnoDB, and

another site handles an average load of 800 inserts/updates per

second in InnoDB.

InnoDB is published under the same GNU GPL

License Version 2 (of June 1991) as MySQL. For more information on

MySQL licensing, see http://www.mysql.com/company/legal/licensing/.

Additional Resources

A forum dedicated to the

InnoDBstorage engine is available at http://forums.mysql.com/list.php?22.Innobase Oy also hosts several forums, available at http://forums.innodb.com.

At the 2008 MySQL User Conference, Innobase announced availability of an

InnoDBPlugin for MySQL. This plugin for MySQL exploits the “pluggable storage engine” architecture of MySQL. TheInnoDB Pluginis included in MySQL 5.5 releases as the built-in version ofInnoDB. The version of theInnoDB Pluginis 1.0.6 as of MySQL 5.5.1 and is considered of Release Candidate (RC) quality.The

InnoDB Pluginoffers new features, improved performance and scalability, enhanced reliability and new capabilities for flexibility and ease of use. Among the features of theInnoDB Pluginare “Fast index creation,” table and index compression, file format management, newINFORMATION_SCHEMAtables, capacity tuning, multiple background I/O threads, and group commit.For information about these features, see the

InnoDB PluginManual at http://www.innodb.com/products/innodb_plugin/plugin-documentation. For general information about usingInnoDBin MySQL, see Section 13.6, “TheInnoDBStorage Engine”.InnoDB Hot Backup enables you to back up a running MySQL database, including

InnoDBandMyISAMtables, with minimal disruption to operations while producing a consistent snapshot of the database. When InnoDB Hot Backup is copyingInnoDBtables, reads and writes to bothInnoDBandMyISAMtables can continue. During the copying ofMyISAMtables, reads (but not writes) to those tables are permitted. In addition, InnoDB Hot Backup supports creating compressed backup files, and performing backups of subsets ofInnoDBtables. In conjunction with MySQL’s binary log, users can perform point-in-time recovery. InnoDB Hot Backup is commercially licensed by Innobase Oy. For a more complete description of InnoDB Hot Backup, see http://www.innodb.com/products/hot-backup/features/ or download the documentation from http://www.innodb.com/doc/hot_backup/manual.html. You can order trial, term, and perpetual licenses from Innobase at http://www.innodb.com/wp/products/hot-backup/order/.

Contact information for Innobase Oy, producer of the

InnoDB engine:

Web site: http://www.innodb.com/

Email: innodb_sales_ww at oracle.com or use

this contact form:

http://www.innodb.com/contact-form

Phone:

+358-9-6969 3250 (office, Heikki Tuuri) +358-40-5617367 (mobile, Heikki Tuuri) +358-40-5939732 (mobile, Satu Sirén)

Address:

Innobase Oy Inc. World Trade Center Helsinki Aleksanterinkatu 17 P.O.Box 800 00101 Helsinki Finland

If you do not want to use InnoDB tables, start

the server with the

--skip-innodb

option to disable the InnoDB startup engine.

Caution

InnoDB is a transaction-safe (ACID compliant)

storage engine for MySQL that has commit, rollback, and

crash-recovery capabilities to protect user data.

However, it cannot do so if the

underlying operating system or hardware does not work as

advertised. Many operating systems or disk subsystems may delay

or reorder write operations to improve performance. On some

operating systems, the very fsync() system

call that should wait until all unwritten data for a file has

been flushed might actually return before the data has been

flushed to stable storage. Because of this, an operating system

crash or a power outage may destroy recently committed data, or

in the worst case, even corrupt the database because of write

operations having been reordered. If data integrity is important

to you, you should perform some “pull-the-plug”

tests before using anything in production. On Mac OS X 10.3 and

up, InnoDB uses a special

fcntl() file flush method. Under Linux, it is

advisable to disable the write-back

cache.

On ATA/SATA disk drives, a command such hdparm -W0

/dev/hda may work to disable the write-back cache.

Beware that some drives or disk

controllers may be unable to disable the write-back

cache.

Two important disk-based resources managed by the

InnoDB storage engine are its tablespace data

files and its log files. If you specify no

InnoDB configuration options, MySQL creates an

auto-extending 10MB data file named ibdata1

and two 5MB log files named ib_logfile0 and

ib_logfile1 in the MySQL data directory. To

get good performance, you should explicitly provide

InnoDB parameters as discussed in the following

examples. Naturally, you should edit the settings to suit your

hardware and requirements.

Caution

It is not a good idea to configure InnoDB to

use data files or log files on NFS volumes. Otherwise, the files

might be locked by other processes and become unavailable for

use by MySQL.

MySQL Enterprise For advice on settings suitable to your specific circumstances, subscribe to the MySQL Enterprise Monitor. For more information, see http://www.mysql.com/products/enterprise/advisors.html.

The examples shown here are representative. See

Section 13.6.3, “InnoDB Startup Options and System Variables” for additional information

about InnoDB-related configuration parameters.

To set up the InnoDB tablespace files, use the

innodb_data_file_path option in

the [mysqld] section of the

my.cnf option file. On Windows, you can use

my.ini instead. The value of

innodb_data_file_path should be a

list of one or more data file specifications. If you name more

than one data file, separate them by semicolon

(“;”) characters:

innodb_data_file_path=datafile_spec1[;datafile_spec2]...

For example, the following setting explicitly creates a tablespace having the same characteristics as the default:

[mysqld] innodb_data_file_path=ibdata1:10M:autoextend

This setting configures a single 10MB data file named

ibdata1 that is auto-extending. No location

for the file is given, so by default, InnoDB

creates it in the MySQL data directory.

Sizes are specified using K,

M, or G suffix letters to

indicate units of KB, MB, or GB.

A tablespace containing a fixed-size 50MB data file named

ibdata1 and a 50MB auto-extending file named

ibdata2 in the data directory can be

configured like this:

[mysqld] innodb_data_file_path=ibdata1:50M;ibdata2:50M:autoextend

The full syntax for a data file specification includes the file name, its size, and several optional attributes:

file_name:file_size[:autoextend[:max:max_file_size]]

The autoextend and max

attributes can be used only for the last data file in the

innodb_data_file_path line.

If you specify the autoextend option for the

last data file, InnoDB extends the data file if

it runs out of free space in the tablespace. The increment is 8MB

at a time by default. To modify the increment, change the

innodb_autoextend_increment

system variable.

If the disk becomes full, you might want to add another data file

on another disk. For tablespace reconfiguration instructions, see

Section 13.6.5, “Adding, Removing, or Resizing InnoDB Data and Log

Files”.

InnoDB is not aware of the file system maximum

file size, so be cautious on file systems where the maximum file

size is a small value such as 2GB. To specify a maximum size for

an auto-extending data file, use the max

attribute following the autoextend attribute.

The following configuration allows ibdata1 to

grow up to a limit of 500MB:

[mysqld] innodb_data_file_path=ibdata1:10M:autoextend:max:500M

InnoDB creates tablespace files in the MySQL

data directory by default. To specify a location explicitly, use

the innodb_data_home_dir option.

For example, to use two files named ibdata1

and ibdata2 but create them in the

/ibdata directory, configure

InnoDB like this:

[mysqld] innodb_data_home_dir = /ibdata innodb_data_file_path=ibdata1:50M;ibdata2:50M:autoextend

Note

InnoDB does not create directories, so make

sure that the /ibdata directory exists

before you start the server. This is also true of any log file

directories that you configure. Use the Unix or DOS

mkdir command to create any necessary

directories.

Make sure that the MySQL server has the proper access rights to create files in the data directory. More generally, the server must have access rights in any directory where it needs to create data files or log files.

InnoDB forms the directory path for each data

file by textually concatenating the value of

innodb_data_home_dir to the data

file name, adding a path name separator (slash or backslash)

between values if necessary. If the

innodb_data_home_dir option is

not mentioned in my.cnf at all, the default

value is the “dot” directory ./,

which means the MySQL data directory. (The MySQL server changes

its current working directory to its data directory when it begins

executing.)

If you specify

innodb_data_home_dir as an empty

string, you can specify absolute paths for the data files listed

in the innodb_data_file_path

value. The following example is equivalent to the preceding one:

[mysqld] innodb_data_home_dir = innodb_data_file_path=/ibdata/ibdata1:50M;/ibdata/ibdata2:50M:autoextend

A simple my.cnf

example. Suppose that you have a computer with 512MB

RAM and one hard disk. The following example shows possible

configuration parameters in my.cnf or

my.ini for InnoDB,

including the autoextend attribute. The example

suits most users, both on Unix and Windows, who do not want to

distribute InnoDB data files and log files onto

several disks. It creates an auto-extending data file

ibdata1 and two InnoDB log

files ib_logfile0 and

ib_logfile1 in the MySQL data directory.

[mysqld] # You can write your other MySQL server options here # ... # Data files must be able to hold your data and indexes. # Make sure that you have enough free disk space. innodb_data_file_path = ibdata1:10M:autoextend # # Set buffer pool size to 50-80% of your computer's memory innodb_buffer_pool_size=256M innodb_additional_mem_pool_size=20M # # Set the log file size to about 25% of the buffer pool size innodb_log_file_size=64M innodb_log_buffer_size=8M # innodb_flush_log_at_trx_commit=1

Note that data files must be less than 2GB in some file systems. The combined size of the log files must be less than 4GB. The combined size of data files must be at least 10MB.

When you create an InnoDB tablespace for the

first time, it is best that you start the MySQL server from the

command prompt. InnoDB then prints the

information about the database creation to the screen, so you can

see what is happening. For example, on Windows, if

mysqld is located in C:\Program

Files\MySQL\MySQL Server 5.5\bin, you can

start it like this:

C:\> "C:\Program Files\MySQL\MySQL Server 5.5\bin\mysqld" --console

If you do not send server output to the screen, check the server's

error log to see what InnoDB prints during the

startup process.

For an example of what the information displayed by

InnoDB should look like, see

Section 13.6.2.3, “Creating the InnoDB Tablespace”.

You can place InnoDB options in the

[mysqld] group of any option file that your

server reads when it starts. The locations for option files are

described in Section 4.2.3.3, “Using Option Files”.

If you installed MySQL on Windows using the installation and

configuration wizards, the option file will be the

my.ini file located in your MySQL

installation directory. See

The Location of the my.ini File.

If your PC uses a boot loader where the C:

drive is not the boot drive, your only option is to use the

my.ini file in your Windows directory

(typically C:\WINDOWS). You can use the

SET command at the command prompt in a console

window to print the value of WINDIR:

C:\> SET WINDIR

windir=C:\WINDOWS

To make sure that mysqld reads options only

from a specific file, use the

--defaults-file option as the

first option on the command line when starting the server:

mysqld --defaults-file=your_path_to_my_cnf

An advanced my.cnf

example. Suppose that you have a Linux computer with

2GB RAM and three 60GB hard disks at directory paths

/, /dr2 and

/dr3. The following example shows possible

configuration parameters in my.cnf for

InnoDB.

[mysqld] # You can write your other MySQL server options here # ... innodb_data_home_dir = # # Data files must be able to hold your data and indexes innodb_data_file_path = /db/ibdata1:2000M;/dr2/db/ibdata2:2000M:autoextend # # Set buffer pool size to 50-80% of your computer's memory, # but make sure on Linux x86 total memory usage is < 2GB innodb_buffer_pool_size=1G innodb_additional_mem_pool_size=20M innodb_log_group_home_dir = /dr3/iblogs # # Set the log file size to about 25% of the buffer pool size innodb_log_file_size=250M innodb_log_buffer_size=8M # innodb_flush_log_at_trx_commit=1 innodb_lock_wait_timeout=50 # # Uncomment the next line if you want to use it #innodb_thread_concurrency=5

In some cases, database performance improves if the data is not

all placed on the same physical disk. Putting log files on a

different disk from data is very often beneficial for performance.

The example illustrates how to do this. It places the two data

files on different disks and places the log files on the third

disk. InnoDB fills the tablespace beginning

with the first data file. You can also use raw disk partitions

(raw devices) as InnoDB data files, which may

speed up I/O. See Section 13.6.2.2, “Using Raw Devices for the Shared Tablespace”.

Warning

On 32-bit GNU/Linux x86, you must be careful not to set memory

usage too high. glibc may allow the process

heap to grow over thread stacks, which crashes your server. It

is a risk if the value of the following expression is close to

or exceeds 2GB:

innodb_buffer_pool_size + key_buffer_size + max_connections*(sort_buffer_size+read_buffer_size+binlog_cache_size) + max_connections*2MB

Each thread uses a stack (often 2MB, but only 256KB in MySQL

binaries provided by Oracle Corporation.) and in the worst case

also uses sort_buffer_size + read_buffer_size

additional memory.

Tuning other mysqld server parameters. The following values are typical and suit most users:

[mysqld]

skip-external-locking

max_connections=200

read_buffer_size=1M

sort_buffer_size=1M

#

# Set key_buffer to 5 - 50% of your RAM depending on how much

# you use MyISAM tables, but keep key_buffer_size + InnoDB

# buffer pool size < 80% of your RAM

key_buffer_size=value

On Linux, if the kernel is enabled for large page support,

InnoDB can use large pages to allocate memory

for its buffer pool and additional memory pool. See

Section 7.5.9, “Enabling Large Page Support”.

You can store each InnoDB table and its

indexes in its own file. This feature is called “multiple

tablespaces” because in effect each table has its own

tablespace.

Using multiple tablespaces can be beneficial to users who want

to move specific tables to separate physical disks or who wish

to restore backups of single tables quickly without interrupting

the use of other InnoDB tables.

To enable multiple tablespaces, start the server with the

--innodb_file_per_table option.

For example, add a line to the [mysqld]

section of my.cnf:

[mysqld] innodb_file_per_table

With multiple tablespaces enabled, InnoDB

stores each newly created table into its own

tbl_name.ibdMyISAM storage engine

does, but MyISAM divides the table into a

tbl_name.MYDtbl_name.MYIInnoDB, the data and the

indexes are stored together in the .ibd

file. The

tbl_name.frm

You cannot freely move .ibd files between

database directories as you can with MyISAM

table files. This is because the table definition that is stored

in the InnoDB shared tablespace includes the

database name, and because InnoDB must

preserve the consistency of transaction IDs and log sequence

numbers.

If you remove the

innodb_file_per_table line from

my.cnf and restart the server,

InnoDB creates tables inside the shared

tablespace files again.

The --innodb_file_per_table

option affects only table creation, not access to existing

tables. If you start the server with this option, new tables are

created using .ibd files, but you can still

access tables that exist in the shared tablespace. If you start

the server without this option, new tables are created in the

shared tablespace, but you can still access any tables that were

created using multiple tablespaces.

Note

InnoDB always needs the shared tablespace

because it puts its internal data dictionary and undo logs

there. The .ibd files are not sufficient

for InnoDB to operate.

To move an .ibd file and the associated

table from one database to another, use a

RENAME TABLE statement:

RENAME TABLEdb1.tbl_nameTOdb2.tbl_name;

If you have a “clean” backup of an

.ibd file, you can restore it to the MySQL

installation from which it originated as follows:

Issue this

ALTER TABLEstatement to delete the current.ibdfile:ALTER TABLE

tbl_nameDISCARD TABLESPACE;Copy the backup

.ibdfile to the proper database directory.Issue this

ALTER TABLEstatement to tellInnoDBto use the new.ibdfile for the table:ALTER TABLE

tbl_nameIMPORT TABLESPACE;

In this context, a “clean”

.ibd file backup is one for which the

following requirements are satisfied:

There are no uncommitted modifications by transactions in the

.ibdfile.There are no unmerged insert buffer entries in the

.ibdfile.Purge has removed all delete-marked index records from the

.ibdfile.mysqld has flushed all modified pages of the

.ibdfile from the buffer pool to the file.

You can make a clean backup .ibd file using

the following method:

Stop all activity from the mysqld server and commit all transactions.

Wait until

SHOW ENGINE INNODB STATUSshows that there are no active transactions in the database, and the main thread status ofInnoDBisWaiting for server activity. Then you can make a copy of the.ibdfile.

Another method for making a clean copy of an

.ibd file is to use the commercial

InnoDB Hot Backup tool:

Use InnoDB Hot Backup to back up the

InnoDBinstallation.Start a second mysqld server on the backup and let it clean up the

.ibdfiles in the backup.

You can use raw disk partitions as data files in the shared tablespace. By using a raw disk, you can perform nonbuffered I/O on Windows and on some Unix systems without file system overhead. This may improve performance, but you are advised to perform tests with and without raw partitions to verify whether this is actually so on your system.

When you create a new data file, you must put the keyword

newraw immediately after the data file size

in innodb_data_file_path. The

partition must be at least as large as the size that you

specify. Note that 1MB in InnoDB is 1024

× 1024 bytes, whereas 1MB in disk specifications usually

means 1,000,000 bytes.

[mysqld] innodb_data_home_dir= innodb_data_file_path=/dev/hdd1:3Gnewraw;/dev/hdd2:2Gnewraw

The next time you start the server, InnoDB

notices the newraw keyword and initializes

the new partition. However, do not create or change any

InnoDB tables yet. Otherwise, when you next

restart the server, InnoDB reinitializes the

partition and your changes are lost. (As a safety measure

InnoDB prevents users from modifying data

when any partition with newraw is specified.)

After InnoDB has initialized the new

partition, stop the server, change newraw in

the data file specification to raw:

[mysqld] innodb_data_home_dir= innodb_data_file_path=/dev/hdd1:3Graw;/dev/hdd2:2Graw

Then restart the server and InnoDB allows

changes to be made.

On Windows, you can allocate a disk partition as a data file like this:

[mysqld] innodb_data_home_dir= innodb_data_file_path=//./D::10Gnewraw

The //./ corresponds to the Windows syntax

of \\.\ for accessing physical drives.

When you use a raw disk partition, be sure that it has

permissions that allow read and write access by the account used

for running the MySQL server. For example, if you run the server

as the mysql user, the partition must allow

read and write access to mysql. If you run

the server with the --memlock

option, the server must be run as root, so

the partition must allow access to root.

Suppose that you have installed MySQL and have edited your

option file so that it contains the necessary

InnoDB configuration parameters. Before

starting MySQL, you should verify that the directories you have

specified for InnoDB data files and log files

exist and that the MySQL server has access rights to those

directories. InnoDB does not create

directories, only files. Check also that you have enough disk

space for the data and log files.

It is best to run the MySQL server mysqld

from the command prompt when you first start the server with

InnoDB enabled, not from

mysqld_safe or as a Windows service. When you

run from a command prompt you see what mysqld

prints and what is happening. On Unix, just invoke

mysqld. On Windows, start

mysqld with the

--console option to direct the

output to the console window.

When you start the MySQL server after initially configuring

InnoDB in your option file,

InnoDB creates your data files and log files,

and prints something like this:

InnoDB: The first specified datafile /home/heikki/data/ibdata1 did not exist: InnoDB: a new database to be created! InnoDB: Setting file /home/heikki/data/ibdata1 size to 134217728 InnoDB: Database physically writes the file full: wait... InnoDB: datafile /home/heikki/data/ibdata2 did not exist: new to be created InnoDB: Setting file /home/heikki/data/ibdata2 size to 262144000 InnoDB: Database physically writes the file full: wait... InnoDB: Log file /home/heikki/data/logs/ib_logfile0 did not exist: new to be created InnoDB: Setting log file /home/heikki/data/logs/ib_logfile0 size to 5242880 InnoDB: Log file /home/heikki/data/logs/ib_logfile1 did not exist: new to be created InnoDB: Setting log file /home/heikki/data/logs/ib_logfile1 size to 5242880 InnoDB: Doublewrite buffer not found: creating new InnoDB: Doublewrite buffer created InnoDB: Creating foreign key constraint system tables InnoDB: Foreign key constraint system tables created InnoDB: Started mysqld: ready for connections

At this point InnoDB has initialized its

tablespace and log files. You can connect to the MySQL server

with the usual MySQL client programs like

mysql. When you shut down the MySQL server

with mysqladmin shutdown, the output is like

this:

010321 18:33:34 mysqld: Normal shutdown 010321 18:33:34 mysqld: Shutdown Complete InnoDB: Starting shutdown... InnoDB: Shutdown completed

You can look at the data file and log directories and you see the files created there. When MySQL is started again, the data files and log files have been created already, so the output is much briefer:

InnoDB: Started mysqld: ready for connections

If you add the

innodb_file_per_table option to

my.cnf, InnoDB stores

each table in its own .ibd file in the same

MySQL database directory where the .frm

file is created. See Section 13.6.2.1, “Using Per-Table Tablespaces”.

If InnoDB prints an operating system error

during a file operation, usually the problem has one of the

following causes:

You did not create the

InnoDBdata file directory or theInnoDBlog directory.mysqld does not have access rights to create files in those directories.

mysqld cannot read the proper

my.cnformy.inioption file, and consequently does not see the options that you specified.The disk is full or a disk quota is exceeded.

You have created a subdirectory whose name is equal to a data file that you specified, so the name cannot be used as a file name.

There is a syntax error in the

innodb_data_home_dirorinnodb_data_file_pathvalue.

If something goes wrong when InnoDB attempts

to initialize its tablespace or its log files, you should delete

all files created by InnoDB. This means all

ibdata files and all

ib_logfile files. In case you have already

created some InnoDB tables, delete the

corresponding .frm files for these tables

(and any .ibd files if you are using

multiple tablespaces) from the MySQL database directories as

well. Then you can try the InnoDB database

creation again. It is best to start the MySQL server from a

command prompt so that you see what is happening.

This section describes the InnoDB-related

command options and system variables. System variables that are

true or false can be enabled at server startup by naming them, or

disabled by using a --skip prefix. For example,

to enable or disable InnoDB checksums, you can

use --innodb_checksums or

--skip-innodb_checksums

on the command line, or

innodb_checksums or

skip-innodb_checksums in an option file. System

variables that take a numeric value can be specified as

--

on the command line or as

var_name=valuevar_name=value

MySQL Enterprise The MySQL Enterprise Monitor provides expert advice on InnoDB start-up options and related system variables. For more information, see http://www.mysql.com/products/enterprise/advisors.html.

Table 13.4. InnoDB Option/Variable

Reference

InnoDB command options:

This option that causes the server to behave as if the built-in

InnoDBis not present. It causes otherInnoDBoptions not to be recognized.Controls loading of the

InnoDBstorage engine, if the server was compiled withInnoDBsupport. This option has a tristate format, with possible values ofOFF,ON, orFORCE.Controls whether

InnoDBcreates a file namedinnodb_status.in the MySQL data directory. If enabled,<pid>InnoDBperiodically writes the output ofSHOW ENGINE INNODB STATUSto this file.By default, the file is not created. To create it, start mysqld with the

--innodb_status_file=1option. The file is deleted during normal shutdown.

InnoDB system variables:

Command-Line Format --ignore-builtin-innodbConfig-File Format ignore_builtin_innodbOption Sets Variable Yes, ignore_builtin_innodbVariable Name ignore_builtin_innodbVariable Scope Global Dynamic Variable No Permitted Values Type booleanWhether the server was started with the

--ignore-builtin-innodboption, which causes the server to behave as if the built-inInnoDBis not present.Command-Line Format --innodb_adaptive_flushing=#Config-File Format innodb_adaptive_flushingOption Sets Variable Yes, innodb_adaptive_flushingVariable Name innodb_adaptive_flushingVariable Scope Global Dynamic Variable Yes Permitted Values Type booleanDefault ONInnoDB Plugin1.0.4 and up uses a heuristic to determine when to flush dirty pages in the buffer cache. This heuristic is designed to avoid bursts of I/O activity and is used wheninnodb_adaptive_flushingis enabled (which is the default).Command-Line Format --innodb_adaptive_hash_index=#Config-File Format innodb_adaptive_hash_indexOption Sets Variable Yes, innodb_adaptive_hash_indexVariable Name innodb_adaptive_hash_indexVariable Scope Global Dynamic Variable Yes Permitted Values Type booleanDefault ONWhether InnoDB adaptive hash indexes are enabled or disabled (see Section 13.6.10.4, “Adaptive Hash Indexes”). This variable is enabled by default. Use

--skip-innodb_adaptive_hash_indexat server startup to disable it.innodb_additional_mem_pool_sizeCommand-Line Format --innodb_additional_mem_pool_size=#Config-File Format innodb_additional_mem_pool_sizeOption Sets Variable Yes, innodb_additional_mem_pool_sizeVariable Name innodb_additional_mem_pool_sizeVariable Scope Global Dynamic Variable No Permitted Values Type numericDefault 8388608Range 2097152-4294967295The size in bytes of a memory pool

InnoDBuses to store data dictionary information and other internal data structures. The more tables you have in your application, the more memory you need to allocate here. IfInnoDBruns out of memory in this pool, it starts to allocate memory from the operating system and writes warning messages to the MySQL error log. The default value is 8MB.Command-Line Format --innodb_autoextend_increment=#Config-File Format innodb_autoextend_incrementOption Sets Variable Yes, innodb_autoextend_incrementVariable Name innodb_autoextend_incrementVariable Scope Global Dynamic Variable Yes Permitted Values Type numericDefault 64Range 1-1000The increment size (in MB) for extending the size of an auto-extending tablespace file when it becomes full. The default value is 8.

Command-Line Format --innodb_autoinc_lock_mode=#Config-File Format innodb_autoinc_lock_modeOption Sets Variable Yes, innodb_autoinc_lock_modeVariable Name innodb_autoinc_lock_modeVariable Scope Global Dynamic Variable No Permitted Values Type numericDefault 1The locking mode to use for generating auto-increment values. The allowable values are 0, 1, or 2, for “traditional”, “consecutive”, or “interleaved” lock mode, respectively. Section 13.6.4.3, “

AUTO_INCREMENTHandling inInnoDB”, describes the characteristics of these modes.This variable has a default of 1 (“consecutive” lock mode).

Command-Line Format --innodb_buffer_pool_size=#Config-File Format innodb_buffer_pool_sizeOption Sets Variable Yes, innodb_buffer_pool_sizeVariable Name innodb_buffer_pool_sizeVariable Scope Global Dynamic Variable No Platform Specific windows Permitted Values Type (windows) numericDefault 134217728Range 5242880-4294967295The size in bytes of the memory buffer

InnoDBuses to cache data and indexes of its tables. The default value is 128MB. The larger you set this value, the less disk I/O is needed to access data in tables. On a dedicated database server, you may set this to up to 80% of the machine physical memory size. However, do not set it too large because competition for physical memory might cause paging in the operating system. Also, the time to initialize the buffer pool is roughly proportional to its size. On large installations, this initialization time may be significant. For example, on a modern Linux x86_64 server, initialization of a 10GB buffer pool takes approximately 6 seconds. See Section 7.4.6, “TheInnoDBBuffer Pool”Command-Line Format --innodb_change_buffering=#Config-File Format innodb_change_bufferingOption Sets Variable Yes, innodb_change_bufferingVariable Name innodb_change_bufferingVariable Scope Global Dynamic Variable Yes Permitted Values Type enumerationDefault insertsValid Values inserts,noneWhether